|

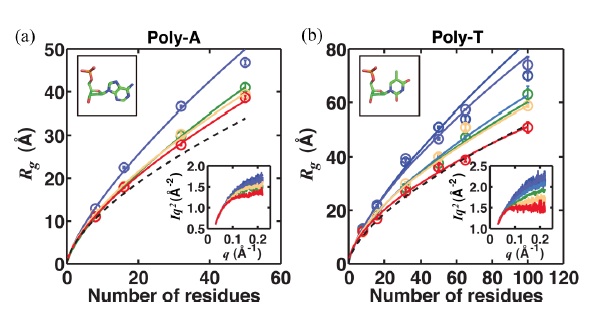

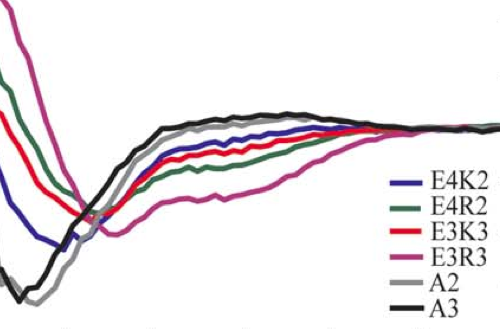

Salt dependence of the radius of gyration and flexibility of single-stranded DNA in solution probed by small-angle x-ray scattering Short single-stranded nucleic acids are ubiquitous in biological processes; understanding their physical properties provides insights to nucleic acid folding and dynamics. We used small-angle x-ray scattering to study 8–100 residue homopolymeric single-stranded DNAs in solution, without external forces or labeling probes. Poly-T’s structural ensemble changes with increasing ionic strength in a manner consistent with a polyelectrolyte persistence length theory that accounts for molecular flexibility. For any number of residues, poly-A is consistently more elongated than poly-T, likely due to the tendency of A residues to form stronger base-stacking interactions than T residues.

|

|

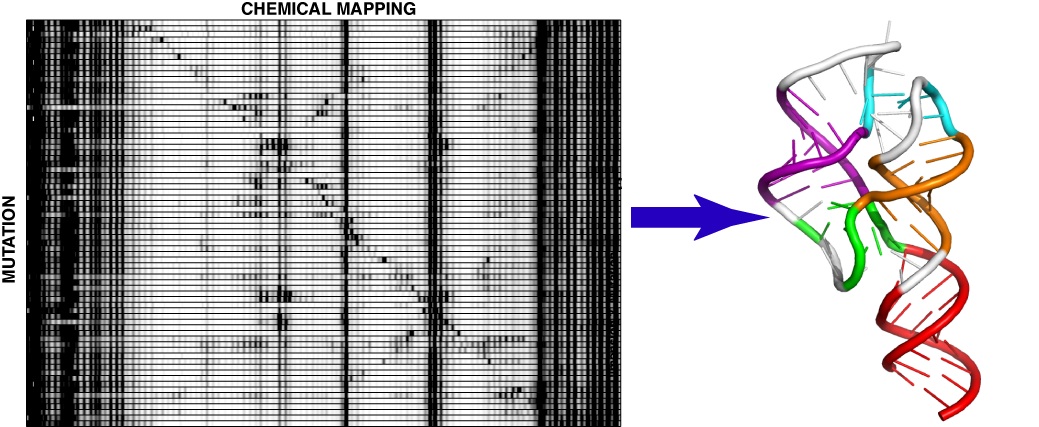

A two-dimensional mutate-and-map strategy for non-coding RNA structure Non-coding RNAs fold into precise base-pairing patterns to carry out critical roles in genetic regulation and protein synthesis, but determining RNA structure remains difficult. Here, we show that coupling systematic mutagenesis with high-throughput chemical mapping enables accurate base-pair inference of domains from ribosomal RNA, ribozymes and riboswitches. For a six-RNA benchmark that has challenged previous chemical/computational methods, this ‘mutate-and-map’ strategy gives secondary structures that are in agreement with crystallography (helix error rates, 2%), including a blind test on a double-glycine riboswitch. Through modelling of partially ordered states, the method enables the first test of an interdomain helix-swap hypothesis for ligand-binding cooperativity in a glycine riboswitch. Finally, the data report on tertiary contacts within non-coding RNAs, and coupling to the Rosetta/FARFAR algorithm gives nucleotide-resolution three-dimensional models (helix root-mean-squared deviation, 5.7 Å) of an adenine riboswitch. These results establish a promising two-dimensional chemical strategy for inferring the secondary and tertiary structures that underlie non-coding RNA behaviour.

|

|

Structure-Function Analysis from the Outside In: Long-Range Tertiary Contacts in RNA Exhibit Distinct Catalytic Roles The conserved catalytic core of the Tetrahymena group I ribozyme is encircled by peripheral elements. We have conducted a detailed structure-funtion study of the five long-range tertiary contacts that fasten these distal elements together. Mutational ablation of each of the tertiary contacts destabilizes the folded ribozyme, indicating a role of the peripheral elements in overall stability. Once folded, three of the five tertiary contact mutants exhibit defects in overall catalysis that range from 20- to 100-fold. These and the subsequent results indicate that the structural ring of peripheral elements does not act as a unitary element; rather, individual connections have distinct roles as further revealed by kinetic and thermodynamic dissection of the individual reaction steps. Ablation of P14 or the metal ion core/metal ion core receptor (MC/MCR) destabilizes docking of the substrate-containing P1 helix into tertiary interactions with the ribozyme's conserved core. In contrast, ablation of the L9/P5 contact weakens binding of the guanosine nucleophile by slowing its association, without affecting P1 docking. The P13 and tetraloop/tetraloop receptor (TL/TLR) mutations had little functional effect and small, local structural changes, as revealed by hydroxyl radical footprinting, whereas the P14, MC/MCR, and L9/P5 mutants show structural changes distal from the mutation site. These changes extended into regions of the catalytic core involved in docking or guanosine binding. Thus, distinct allosterical pathways couple the long-range tertiary contacts to functional sites within the conserved core. This modular functional specialization may represent a fundamental strategy in RNA structure-function interrelationships.

|

|

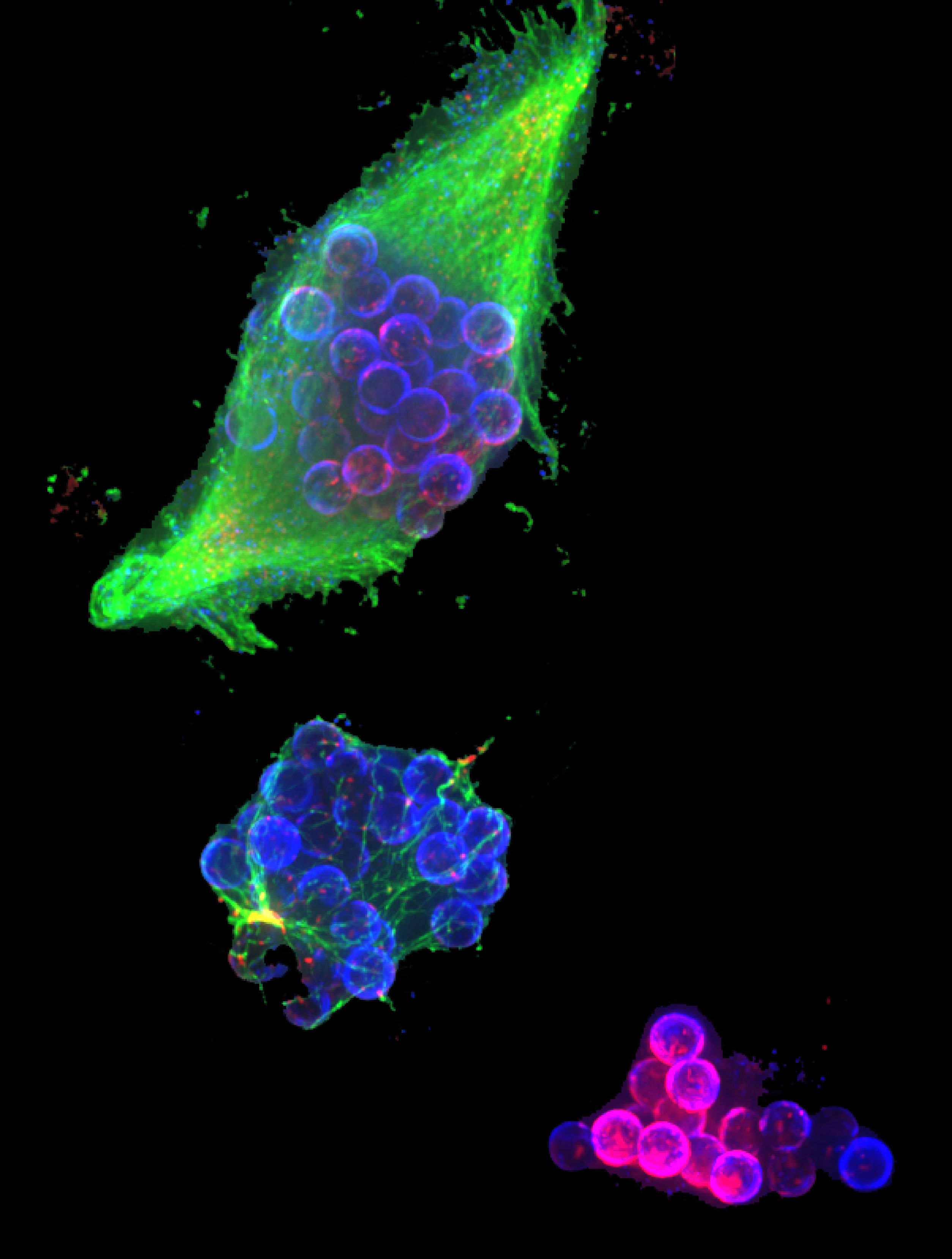

n vitro centromere and kinetochore assembly on defined chromatin templates During cell division, chromosomes are segregated to nascent daughter cells by attaching to the microtubes of the mitotic spindle through kinetochore. Kinetochores are assembled on a specialized chromatin domain called the centromere, which is characterized by the replacement of nucleosomal histone H3 with the histone H3 variant centromere protein A (CENP-A). CENP-A is essential for centromere and kinetochore formation in all eukaryotes but it is unknown how CENP-A chromatin directs centromere and kinetochore assembly. Here we generate synthetic CENP-A chromatin that recapitulates the essential steps of centromere and kinetochore assembly in vitro. We show that reconstituted CENP-A chromatin when added to cell-free extracts is sufficient for the assembly of centromeres and kinetochore proteins, microtubule binding and stabilization, and mitotic checkpoint function. Using chromatin assembled from histone H3/CENP-A chimaeras, we demonstrate that the conserved carboxy terminus of CENP-A is necessary and sufficient for centromere and kinetochore protein recruitment and function but that the CENP-A targeting domain - required for new CENP-A histone assembly - is not. These data show that two of the primary requirements for accurate chromosome segregation, the assembly of the kinetochore and the propagation of CENP-A chromatin, are specified by different elements in the CENP-A histone. Our unique cell-free system enables complete control and manipulation of the chromatin substrate and thus presents a powerful tool to study centromere and kinetochore assembly.

|

|

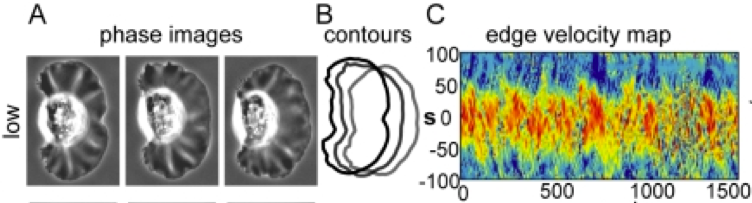

An Adhesion-Dependent Switch between Mechanisms That Determine Motile Cell Shape Keratocytes are fast-moving cells in which adhesion dynamics are tightly coupled to the actin polymerization motor that drives migration, resulting in highly coordinated cell movement. We have found that modifying the adhesive properties of the underlying substrate has a dramatic effect on keratocyte morphology. Cells crawling at intermediate adhesion strengths resembled stereotypical keratocytes, characterized by a broad, fan-shaped lamellipodium, clearly defined leading and trailing edges, and persistent rates of protrusion and retraction. Cells at low adhesion strength were small and round with highly variable protrusion and retraction rates, and cells at high adhesion strength were large and asymmetrical and, strikingly, exhibited traveling waves of protrusion. To elucidate the mechanisms by which adhesion strength determines cell behavior, we examined the organization of adhesions, myosin II, and the actin network in keratocytes migrating on substrates with different adhesion strengths. On the whole, our results are consistent wtih a quantitative physical model in which keratocyte shape and migratory behavior emerge from the self-organization of actin, adhesions, and myosin, and quantitative changes in either adhesion strength or myosin contraction can switch keratocytes among qualitatively distinct migration regimes.

|

|

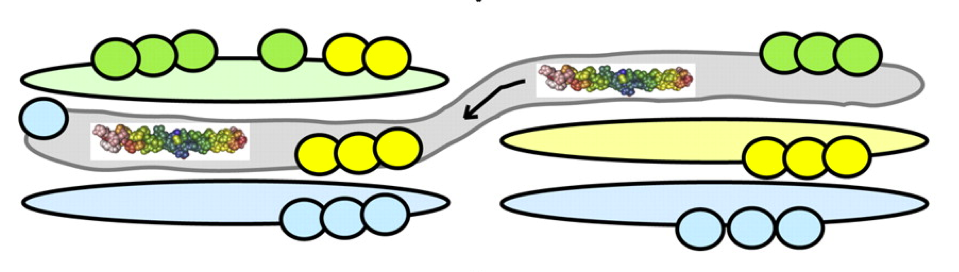

How the Golgi works: A cisternal progenitor model The Golgi complex is a central processing component in the secretory pathway of eukaryotic cells. This essential component processes more than 30% of the proteins encoded by the human genome, yet we will do not fully understand how the Golgi is assembled and how proteins pass through it. Recent advances in our understanding of the molecular basis for protein transport through the Golgi and within the endocytic pathway provide clues to how this complex organelle may function and how proteins may be transported through it. Described here is a possible model for transport of cargo through a tightly stacked Golgi that involves continual fusion and fission of stable, "like" subcompartments and provides a mechanism to grow the Golgi complex from a stable progenitor, in an ordered manner. READ FULL PUBLICATION

|

|

Helicity of short E-R/K peptides

|

|

A molecular inversion probe assay for detecting alternative splicing |

|

Centromere assembly requires the direct recognition of CENP-A nucleosomes by CENP-N Centromeres are specialized chromosonal domains that direct kinetochore assembly during mitosis. CENP-A (centromere protein A), a histone H3-variant present exclusively in centromeric nucleosomes, is thought to function as an epigenetic mark that specifies cetromere identity. Here we idently the essential centromere protein CENP-N as the first protein to selectively bind CENP-A nucleosomes but not H3 nuclesomes. CENP-N bound CENP-A-H4 tetramers. Mutations in CENP-N that reduced its affinity for CENP-A nucleosomes caused defects in CENP-N localization and had dominant effects on the recruitment of CENP-H, CENP-I and CENP-K to centromere. Depletion of CENP-N using siRHA (short interfering RNA) led to similar centromere assembly defects and resulted in reduced assembly of nascent CENP-A into centromeric chromatin. These data suggest that CENP-N interprets the information encoded within CENP-A nucleosomes and recruits other proteins to centromeric chromatin that are required for centromere function and propagation.

|