Alison Pidoux 2012 |

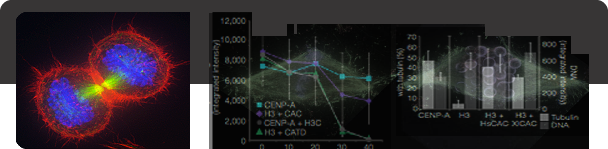

Centromere and Kinetochore Assembly The key site for attachment of the chromosome to the mitotic spindle is the kinetochore. Kinetochores demonstrate amazing structural diversity: budding yeast employ a minimalist kinetochore that binds a single microtubule, human kinetochores bind approximately 20 microtubules, and nematode worms expand their kinetochores so that they occupy the entire length of the chromosome. Despite organizational differences, many of the core proteins of the kinetochore are conserved throughout eukaryotes. We are attempting to understand the underlying principles that give rise to this diversity of kinetochore structures but still allow the common function of microtubule binding during mitosis. The kinetochore is a transient structure that only exists during mitosis and is disassembled after cells |

Terry Winters 2000 |

Chromosome Segregation We are studying the process of chromosome segregation in eukaryotic cells. Accurate chromosome segregation is critical to ensure that cells are duplicated without genome loss or damage. Chromosome segregation mechanisms are conserved from yeast cells to humans. Chromosomes are replicated during S-phase and are then segregated by a microtubule spindle during mitosis. We are interested in understanding how the chromosomes attach to the microtubule spindle during |

RNA Inc. |

RNA Directed Chromatin Modification Noncoding RNAs play essential roles in regulating the organization of chromatin domains. Two of the most well studied examples are the Xist RNA in humans that is required silencing transcription of one X chromosome in females so that the proper gene dosage is maintained between male and female cells and the short RNAs used by the RNA interference machinery in fission yeast to form heterochromatin at centromeres and ensure accurate chromosome segregation. In both of these examples, RNA molecules direct the modification of chromosomes resulting in changes in chromatin organization, transcriptional output and the functional properties of the chromosome. Although the importance of RNA in the process of chromosome specialization is widely appreciated, the mechanisms through which RNAs guide the modification and reorganization of chromatin domains are only beginning to be understood. Recent efforts in our laboratory have focused on RNAs that are associated with vertebrate mitotic |

Matthew Ritchie 2004 |

Chromosome Structure Chromosomes undergo dynamic structural changes during the cell cycle and during cell differentiation that dictate the functional properties of the chromosome. One of the most dramatic examples of this is the mitotic condensation of chromosomes that is required for chromosome segregation during cell division. We currently have a very limited understanding of the higher order folding of the chromosome. The X-ray crystal structure of the nucleosome has provided a detailed understanding of the primary level of organization of the chromosome (Luger et al, Nature 1997). However, the organization of the chromosome beyond the wrapping of DNA around the nucleosome is unknown and the mechanisms that control chromosome structural rearrangement are only beginning to be deciphered. We are developing techniques to map the higher order folding of chromosomes from the nucleosome |